The Desert Fathers emerged in Egypt. Perhaps as early as the late 200’s AD, these Egyptian Christian men left the pagan cities, the persecutions and the distractions of life to live as hermits in the Sahara Desert. Their purpose was to live a solitary life solely dedicated to God.

The Desert Fathers emerged in Egypt. Perhaps as early as the late 200’s AD, these Egyptian Christian men left the pagan cities, the persecutions and the distractions of life to live as hermits in the Sahara Desert. Their purpose was to live a solitary life solely dedicated to God.

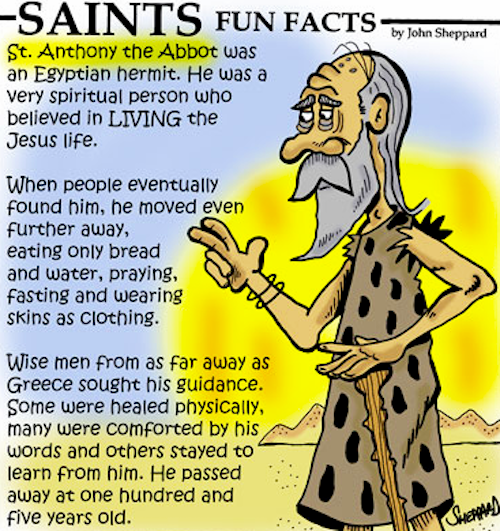

A wealthy, young Christian man, Anthony of Egypt (c. 251-356), gave away all his inherited riches and retired to a hut in the desert. His very long and influential life as a hermit precipitated what has been called “the peopling of the desert.” After his biographer Bishop Athanasius (293-373) published his Vitae Antonii extolling Anthony’s life, flocks of Christian men and women came to Egypt to live the anchoritic life exemplified by St. Anthony.

A saying of St. Anthony: “To those who have an active belief, reasoned proofs are needless and probably useless.”

Soon the desert around Egypt’s major cities was filled with people living in individual cells they had built with their own hands. They wove baskets to sell, formed loose-knit communities and devoted themselves to labor, solitude and prayer. With the blood persecutions over in 313 with the Edict of Milan giving Christians the right to worship, some Christians began to embrace a “white martyrdom” in which the flesh was mortified so that the spirit might live.

Another Egyptian from Thebes named Pachomius (292-348) was one of the founders of modern communal monastic life.

When he was 20, he was imprisoned by the Romans. Local Christians brought him and other prisoners food and other necessities every day. According to Aristides, the 2nd century apologist, Christians typically ministered not only to their brothers and sisters who were in prison for the faith, but to all prisoners as a witness to Christian charity and care:

“(Christians) help those who offend them, making friends of them; do good to their enemies….When they meet strangers, they invite them to their homes with joy….When a poor man dies, if they become aware, they contribute according to their means for his funeral; if they come to know that some people are persecuted or sent to prison or condemned for the sake of Christ’s name, they put their alms together and send them to those in need. If they can do it, they try to obtain their release.” Apology 15

Because of the kindness of Christians to people they did not even know, Pachomius became a Christian when he was released from prison in c. 314. Jesus had said to His followers:

“’For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’” Matthew 25:35-40

Pachomius felt drawn to the Desert Fathers and built his cell in the desert near St. Anthony. But Pachomius saw that most of the men who desired Anthony’s eremitic life could not live in such solitary isolation. He decided to build 10 to 12 room houses where men could live together in individual rooms and practice, if they so chose, certain mortifications of the flesh such as celibacy, obedience, poverty and/or self-sufficiency. These early monasteries, and soon nunneries, had no Biblical mandates or foundations but were an outgrowth of the human desire to follow God without the normal daily distractions. Even though there had been monastic groups before Pachomius, he is called the “Father of Cenobitic Monasticism.” “Cenobitic” comes from the two Greek words koinos meaning “common, shared by many” and bios meaning “life.” Pachomius’ “communal living” was the opposite of Anthony’s solitary, hermitic life. The genius was that he had combined the reclusive life of the individual cells with the communal life of corporate meals, work and worship. Pachomius remained monastic his whole life and refused to be ordained as a priest. At his death on May 9, 348 more than 3,000 of his small “monasteries” dotted the Egyptian desert.

1,700 years later there are still 11 Christian monasteries (from the Greek monazein meaning “to live alone”) scattered throughout the Sahara Desert in Egypt.

Outside of Cairo in Wadi Natroun (Coptic natroun meaning “salt” as in “valley of salt”) there are today four Coptic Orthodox monasteries that welcome visitors, Christian and Muslim. The cloistered life has always had an appeal for religious as well as philosophical people. Even in the time of Jesus, the Jewish Essenes and another group called the Therapeutae were people who lived according to strict ascetic rules outside of society in the Judean desert.

Many of the Desert Fathers in those early centuries have left golden nuggets of wisdom:

“This is the truth. If a man regards contempt as praise, poverty as riches and hunger as feast, he will never die.” Macarius (d. 395)

“This is the great work of man: always to take the blame for his own sins before God and to expect temptation to his last breath.” St. Anthony (251-356)

“I consider no other labor as difficult as prayer. When we are ready to pray, our spiritual enemies interfere. They understand it is only by making it difficult for us to pray that they can harm us. Other things will meet with success if we keep at it, but laboring at prayer is a war that will continue until we die.” Abba Agathon (3rd century)

“Love is to find a leper, to take his body, and gladly give him your own.” Abba Agathon

At the time of the Desert Fathers, the Early Church had not established the offices of nuns and monks. The tremendous attraction the Desert Fathers had on clergy and laity after the Roman persecutions were over, however, laid the foundations for the monasteries and the nunneries of the Roman church in the West from the 5th through the 10th centuries. Some early Christians, like the Desert Fathers, chose the “white martyrdom” of the anchoritic life. — Article by Sandra Sweeny Silver