“Thus says the Lord: ‘Stand by the roads, and look, and ask for the ancient paths, where the good way is; and walk in it, and find rest for your souls.’’’ Jeremiah 6:16

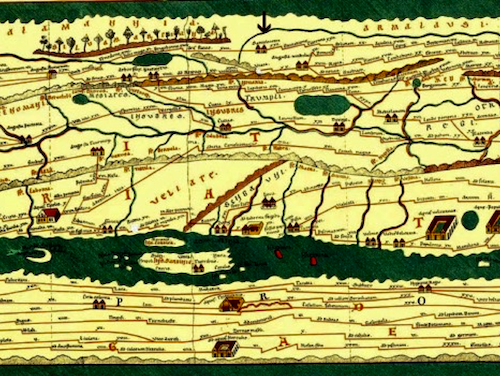

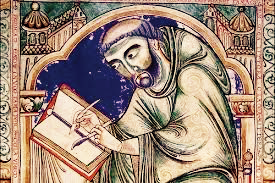

The eleven sheets of the ancient Peutinger Map (Tabula Peutingeriana) are in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, Austria. At 22 feet long and a scant 14 inches high, it is a hand-made parchment map of the state-run public roads, the cursus publicus, of the ancient Roman Empire replicated in the 1200’s by a medieval monk in Colmar, France.

The eleven sheets of the ancient Peutinger Map (Tabula Peutingeriana) are in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, Austria. At 22 feet long and a scant 14 inches high, it is a hand-made parchment map of the state-run public roads, the cursus publicus, of the ancient Roman Empire replicated in the 1200’s by a medieval monk in Colmar, France.

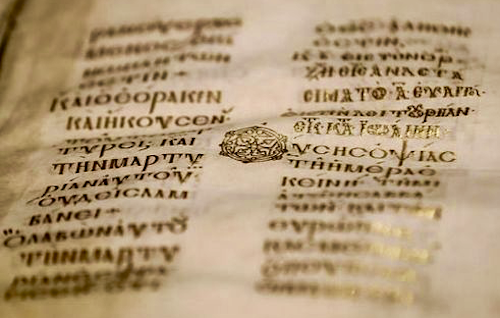

The Peutinger Map is a reproduction of a 300-400’s AD map found, likely, in an old French monastery. That would not be unusual. In May of 1975 in the Greek monastery of St. Catherine, built c. 550, at the foot of Mt. Sinai, Father Sofronius discovered 47 ragged cartons full of manuscripts and icons. Included in the cache were old fragments of Homer’s Iliad, very early texts of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John and other valuable fragments. Now the St. Catherine monastery has begun a high-tech process of digitizing all of its 4,500 manuscripts.

The 1200’s Peutinger parchment map, transcribed by an unknown monk, was lost and re-discovered in 1494 in a library in Worms, Germany by Conrad Celtes. He knew its value but was not able to publish it. On his death, it was bequeathed to German antiquarian Konrad Peutinger.

The Peutinger family kept the eponymous Peutinger Map for several hundred years until it was sold in 1714 to German royalty and ended up in the Imperial Court Library at Hofburg (meaning “Castle of the Court”) palace in Vienna.

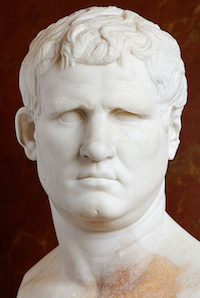

The recovered c. 300’s-400’s AD map the monk replicated in the 1200’s was itself a replica of the original map prepared, perhaps, by Marcus Agrippa, 63—12 BC (left) in the first century BC during Emperor Augustus’ reign beginning in 27 BC and ending with his death in 14 AD. Marcus Agrippa was Augustus Caesar’s best friend.

The recovered c. 300’s-400’s AD map the monk replicated in the 1200’s was itself a replica of the original map prepared, perhaps, by Marcus Agrippa, 63—12 BC (left) in the first century BC during Emperor Augustus’ reign beginning in 27 BC and ending with his death in 14 AD. Marcus Agrippa was Augustus Caesar’s best friend.

If Agrippa fashioned/oversaw the original map, that would make the 300-400’s AD map a replica of the original map done by Agrippa before his death in 12 BC. The 1200’s Peutinger Map, if these calculations are true, is a replica of a replica of the original map..

The map tracks all of Rome’s public roads stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to modern-day Sri Lanka (7,645 miles). All told the map contains 124,274 main and ancillary Roman roads. The Romans built roads which lead through more than 550 cities and over 3,500 types of named topography (rivers, oceans, deserts, mountains, etc.). Needless to say, all the places and features had to be unnaturally crushed into the small 14” high space of the map.

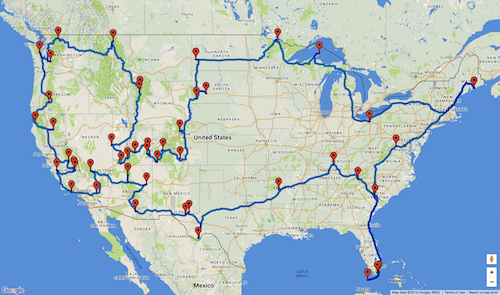

The Pharos Lighthouse (below in center) in Alexandria, Egypt, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, is in the middle next to the Mediterranean Sea. The Peutinger Map is similar in idea to our road maps today.

The Peutinger Map is similar in idea to our road maps today. Rome was at the very center of the map. Of course, all (red) roads led to Roma. Here the Eternal City is seated on a throne. He has a globe and sceptre in his hands. All roads led to Rome—Roma, caput Mundi, qui regis orbis frena rotundi—“Rome, capital of the world, who holds the bridles of the Globe,” as they said.

Rome was at the very center of the map. Of course, all (red) roads led to Roma. Here the Eternal City is seated on a throne. He has a globe and sceptre in his hands. All roads led to Rome—Roma, caput Mundi, qui regis orbis frena rotundi—“Rome, capital of the world, who holds the bridles of the Globe,” as they said. The 300’s—400’s cartographer has, also, added some short comments on landscapes known from the Bible. For example, in his depiction of the Sinai desert, we read that Moses and the children of Israel wandered here for forty years. So even in that ancient time, Moses was considered an historical figure and the Exodus was considered an historical event.

The 300’s—400’s cartographer has, also, added some short comments on landscapes known from the Bible. For example, in his depiction of the Sinai desert, we read that Moses and the children of Israel wandered here for forty years. So even in that ancient time, Moses was considered an historical figure and the Exodus was considered an historical event.

Imperial Rome was in the 300’s and 400’s waging a war against an enemy which had no empire, no weapons, no money and no equipment except its faith in a Risen Savior named Jesus of Nazareth. That unlikely army won the war in 313 AD with the Edict of Milan. Rome had for several centuries been going down a wrong, broad road.—Sandra Sweeny Silver