In the gladiators the Romans found the ideal representation of their brave soldiers. Here were the strongest, the most elite of the conquered tribes. Here were trained, trim and toned men fighting for their lives.

There were four schools to train gladiators in Rome, the largest of which, Ludus Magnus, was connected to the Colosseum by an underground tunnel

On the day of the fight, the pairs of gladiators walked the long dark tunnel to the arena and watched as their friends fought and died. They waited their turn.

The gladiators were paired according to their defensive and offensive weapons. A Thracian with his curved short sword and armor on his left arm was paired with a Mirmillo who had a small shield, a lance and a crested helmet with a vizor. A Retarius had a net, a trident, a dagger and scaled armor covering his left arm. He would be paired with a Secutor who had a shield, a sword and a full helmet.

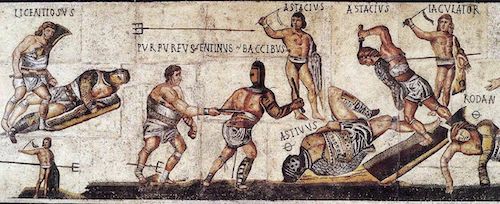

Attesting to the wild popularity of these fighters, archaeologists have unearthed stunning mosaics of gladiators all over the Roman Empire. At the Borghese estate in Torrenova in 1834, they found the floor of a dining room from c. 320 rimmed with sixteen fields of mosaics relating to gladiators.

In one square a gladiator is being prodded by a hot iron to continue fighting. Many of the squares show them fighting, dying, bleeding. An interesting square shows musicians playing. This confirms what some ancient authors have written. An orchestra played extemporaneously along with the fights, with a slow tempo as they circled each other and a fast tempo as one moved in for the kill.

Another mosaic found in 2007 in the ruins of Emperor Commodus’ palace in Rome depicts a Retarius gladiator named Montanus being proclaimed victor by a referee named Antonius. Commodus was the handsome, muscular Emperor (reigned 180-192) who fashioned himself a gladiator. He often performed mock feats of Hercules to prove his virility and even fought naked in the arena to the disgust of the spectators. Of course, he always won because the whole charade was an exercise in vanity.

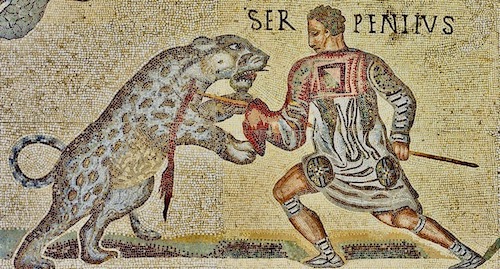

In the Museo Nazionale in Rome there is a limestone relief of a Roman gladiator with helmet and shield fighting off a leopard attacking him on the left but looking to an approaching lion on his right that is being goaded to attack him by a man holding an iron prod. It is unclear whether this gladiator is a trained fighter or a criminal or Christian dressed like a gladiator, but there are rare instances where gladiators were made to fight wild animals.

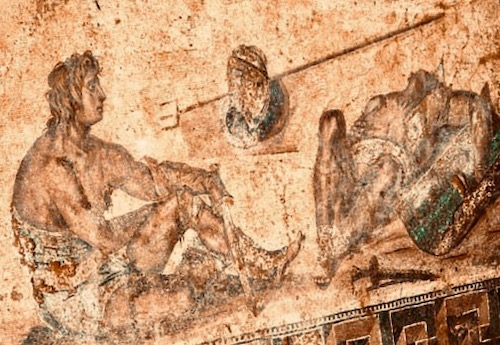

Another exquisite mosaic of a gladiator was unearthed on the coast of Libya in 2000. An exhausted, victorious gladiator is seated on the arena sand and is staring at his dead opponent (below). Those who have seen the mosaic and gazed into the gladiator’s eyes say the sad, exhausted and jaded look is worthy of a Botticelli. Lactantius (c. 240-320), who was an advisor to the first Christian Emperor Constantine, critiques the Colosseum contests and adjures Christians not to go to them:

Lactantius (c. 240-320), who was an advisor to the first Christian Emperor Constantine, critiques the Colosseum contests and adjures Christians not to go to them:

“He who finds it pleasurable to watch a man being killed even though the man has been legally condemned, pollutes his conscience just as much as though he were an accomplice or willing spectator of a murder committed in secret. Yet they call these ‘sports’ where human blood is shed! When you see men placed under the stroke of death, begging for mercy, can they be righteous when they not only permit the men to be killed but demand it? They cast their cruel and inhuman votes for death, not being satisfied by the mere flowing of blood or the presence of gashing wounds. In fact, they order the (gladiators), although wounded and lying on the ground, to be attacked again and their corpses to be pummeled with blows to make certain they are not merely feigning death. The crowds are even angry with the gladiators if one of the two isn’t slain quickly. As though they thirsted for human blood, they hate delays….By steeping themselves in this practice, they have lost their humanity. Therefore, it is not fitting that we who strive to stay on the path of righteousness should share in this public homicide.” Divine Institutes 7.20

Constantine outlawed the contests in 325 AD. One of the triumphs of Christianity was the last gladiator fight in Rome on January 1, 404.

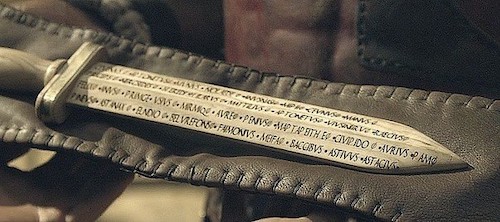

Certainly these brave gladiators were worthy of praise. The best among them became public idols—valiant men fighting and vanquishing opponent after opponent, year after year. The crowd loved the superstar gladiators. So did the women.  “Gladiator,” coming from the Latin word for the 23” steel sword they used (the gladius), was, also, a slang term for “penis.” Gladiators who won consistently became national heroes and had groupies. Young women, middle-aged women and old women hung around the gladiator barracks just to get a look at a famous fighter. Because Pompeii was destroyed in one day and entombed in volcanic ash, many wall inscriptions and artifacts have survived in tact. Written on the wall of a gladiator school is: “The Thracian Celadus is the heartthrob of all the girls.” In that same school was found the skeleton of a richly adorned woman. Was she having a liaison with a gladiator? Or did she just take shelter from the rain of volcanic ash? We will never know.

“Gladiator,” coming from the Latin word for the 23” steel sword they used (the gladius), was, also, a slang term for “penis.” Gladiators who won consistently became national heroes and had groupies. Young women, middle-aged women and old women hung around the gladiator barracks just to get a look at a famous fighter. Because Pompeii was destroyed in one day and entombed in volcanic ash, many wall inscriptions and artifacts have survived in tact. Written on the wall of a gladiator school is: “The Thracian Celadus is the heartthrob of all the girls.” In that same school was found the skeleton of a richly adorned woman. Was she having a liaison with a gladiator? Or did she just take shelter from the rain of volcanic ash? We will never know.

But we do know the story of Eppia and her gladiator lover Sergius. It is the most famous ancient account of a romance between a gladiator and a noble woman. Juvenal (c. 57-127) tells the story in his Satires 6:

But we do know the story of Eppia and her gladiator lover Sergius. It is the most famous ancient account of a romance between a gladiator and a noble woman. Juvenal (c. 57-127) tells the story in his Satires 6:

“Eppia, though the wife of a senator, went off with a gladiator to Pharos and the Nile on the notorious walls of Alexandria, though even Egypt condemns Rome’s disgusting morals. Forgetting her home, her husband and her sister, she showed no concern whatever for roman Eppia and her gladiator lover her homeland…and her children in tears…When she was a baby she was pillowed in great luxury in the down of her father’s mansion in a cradle of the finest workmanship…She didn’t worry about the dangers of sea travel—She had long since stopped worrying about her reputation….With heart undaunted she braved the waves of the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea to get to Egypt….Yet what was the glamour that set her on fire, what was the prime manhood that captured Eppia’s heart? What was it she saw in him that would compensate for her being called ‘gladiatrix?’

Note that her lover, dear Sergius, had now started shaving his neck and was hoping to be released from duty (as a gladiator) because of a bad wound on his arm. Moreover, his face was deformed in a number of ways. He had a mark where his helmet rubbed him and a big wart between his nostrils and a smelly discharge dripping from his eye. But he was a gladiator! That made him…beautiful. This is what she preferred to her children and her homeland, her sister and her husband. It’s the sword they’re in love with!”

Not all gladiator fights resulted in the death of one of the gladiators. If both had fought valiantly to a draw, the crowd insisted they both be spared. On the opening day of the Colosseum in 81, two famous gladiators, Priscus and Verus (below), were to fight each other to the death: “As Priscus and Verus each lengthened the contest and for a long time the battle was equal on each side, repeatedly loud shouts petitioned for the men to be released. But Caesar (Titus) followed his own law. It was the law to fight without shield until a finger was raised….But an end was found to the equal division: Equals to fight, equals to yield. Caesar sent wooden swords to both and (victor’s) palms to both. Thus skillful courage received its prize. This took place under no prince except you, Caesar, when two fought, both were victor.” Martial, On The Spectacles 29

“As Priscus and Verus each lengthened the contest and for a long time the battle was equal on each side, repeatedly loud shouts petitioned for the men to be released. But Caesar (Titus) followed his own law. It was the law to fight without shield until a finger was raised….But an end was found to the equal division: Equals to fight, equals to yield. Caesar sent wooden swords to both and (victor’s) palms to both. Thus skillful courage received its prize. This took place under no prince except you, Caesar, when two fought, both were victor.” Martial, On The Spectacles 29

Sometimes the loser had fought so well that the emperor and the crowd wanted him to live. Occasionally a superstar gladiator was given his freedom if he had fought victoriously for many years. Some gladiators had fought and won so many times over so many years that they were retired with acclamation. Suetonius writes of one such gladiator:

“….when (Claudius) had granted the wooden sword to a gladiator whose four sons had begged for his discharge, the (public) act (in the arena) was received with loud and general applause.” Lives of the Caesars: Claudius

Wounded and scarred as he was, Eppia’s lover Sergius, the victorious veteran of many fights, was probably retired. When a gladiator was given retirement, he was presented with a wooden sword, a symbol of “no more blood.” Often the man chose to remain at the school as an instructor. Not Sergius. He left for Egypt and took his pampered Eppia with him.—Sandra Sweeny Silver