When the leaky Mayflower floundered on the cold November shores of the New World, the Pilgrims were half-starved, half-crazed and holy grateful. The Spartan stores of biscuits, salted beef and stale beer were almost exhausted.  An exploration party led by Myles Standish (1584-1656) found baskets of seed corn buried by the Wampanoag Indians in a hill nearby. This sturdy yellow kernel, indigenous to the Americas, was to become a basic staple not only for the Founding Families but for the whole world.

An exploration party led by Myles Standish (1584-1656) found baskets of seed corn buried by the Wampanoag Indians in a hill nearby. This sturdy yellow kernel, indigenous to the Americas, was to become a basic staple not only for the Founding Families but for the whole world.

That first winter the Saints, clinging to the craggy beaches of the New World, died of scurvy, pneumonia, tuberculosis, starvation and ignorance. They were ignorant of the land and its cornucopia of cures, foods and fuels. Then came Spring and Squanto.

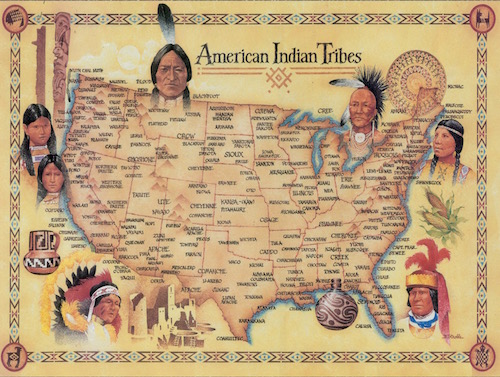

This English-speaking Indian had been captured c. 1610 and taken to Plymouth, England. Some think Squanto recrossed the Atlantic with Captain John Smith in 1614. Squanto’s routes and roots are vague, but one thing is clear. He was a Godsend for the English settlers. As William Bradford wrote “Squanto was a speciall instrumente sent of God for [our] good and beyond [our] expectation.” Squanto not only shared their lives, but within a year he had come to know the God Who had brought the Pilgrims to this land.

As the New England Spring warmed the earth, Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to plant corn for the harvest—four kernels to a hillock. He invited them to taste and to cook the yellow and green squash that the immigrants had thought inedible and the blood red berries in the cranberry bogs they had felt were poisonous.

He beckoned, “Here is food”: herring from the Plymouth Town Brook. “This is food”: the red tomatoes that hung from fat stems. (Later the tomato would be considered poisonous until the late 1600’s.) “Dig here for food”: earthy, long tubers of white potatoes. “Watch. This is the best”: strip the bark from this tree and watch the sap leak out. Get buckets. Boil it. Maple syrup. Yum! Even the trees of the New World were good to eat.

All of these foods and hundreds more as we pushed westward were sent back to the Old World as prizes. The white potato so common now in Europe was indigenous to the Americas. When it was introduced to Europe in the 1500’s, its journey started in Italy where its arrival coincided with the out-break of a disease. The Italians blamed the pestilence on the potato, so the spud was shoved north where the Germans loved it, the French fried it and the Irish built an economy on it. All the natural wealth and wonder of America the Bountiful was poured into the Pilgrims by Squanto and the friendly Indians.

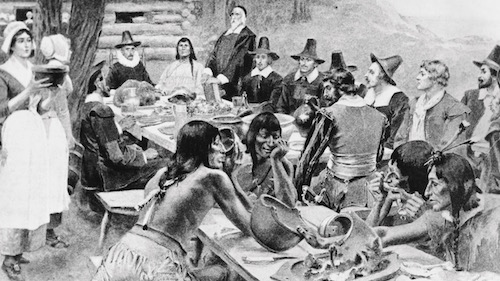

When the Fall harvest of corn and squash and beans and grapes and berries and nuts was combined with catches of fish and fowl, the Pilgrims invited the Wampanoags to a Thanksgiving to God Feast.

The Indians brought five deer and stayed three days. In addition to the venison and vegetables, they ate lobsters, fat eel pies, corn bread and “sallet herbes” from the wild greens. This first Thanksgiving was celebrated in October. Our November date was established by President Abraham Lincoln who made it an official holiday in 1863.

One can imagine the warm Indian Summer sun filtering through the Fall foliage on the First Feast—the Pilgrims with their faith tested and triumphing and the Indians with their innocence wondering and waning.

One can imagine the holy sojourners who had braved a New World and the holy hunters who had made them welcome.—Sandra Sweeny Silver