When a child was born, he/she was laid at the feet of the paterfamilias, the head of the family household, usually the father of the child. Raising the newborn up in his arms, he acknowledged the child as his own and a member of his household. If he examined the child at his feet and found it was defective in some way, the baby was occasionally given to a nurse or household slave to be abandoned on one of the garbage dumps or dung heaps of the city.

CLICK TO READ Infanticide in the Ancient World

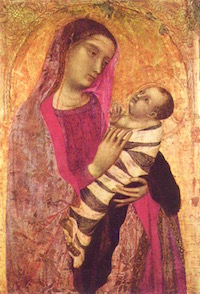

For thousands of years newborns/babies have been “swaddled” (wrapped in cloths). The most famous “swaddled Baby” was Jesus of Nazareth: “And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.” Luke 2:12 (c. 59-63 AD)

After the swaddled child had been accepted into the family, a bulla was hung around the boy’s neck. The bulla was a gold (if the family was wealthy) or a leather pouch containing amulets to ward off evil spirits. The thought was that children were particularly vulnerable to evil and disease. The boy’s bulla contained phallic objects. A lunula, a crescent-shaped necklace, was hung around the girl’s neck as her protection.

There seems to have been a more intentional graduation of garments for the boys in Rome than for the girls. When the boy became a man between the ages of 14 and 17, he took off the bulla and gave it to the gods. When a girl was married between the ages of 14 to 16, she took off her lunula on the eve of her wedding day. Both lunulas and bullas were worn on a chain, cord or strap around the neck.

Children were not considered really “people” until they reached the ages of 5-7 probably because there was a high mortality rate for children. When they became little girls, they wore a long plain white tunic with a woolen/leather belt tied around their waists.

High-born little boys wore a tunic with a purple or red border that reached to their knees. The colored border declared they were freeborn and of a good family.

If it was cold outside, both children wore a cloak. After Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58-50 BC) in France/Germany, Romans adopted the pants/trousers they had seen soldiers wearing in the colder climates. Notice the modern Celtic pattern on this boy’s tunic (left), the bulla around his neck and the trousers.

If it was cold outside, both children wore a cloak. After Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58-50 BC) in France/Germany, Romans adopted the pants/trousers they had seen soldiers wearing in the colder climates. Notice the modern Celtic pattern on this boy’s tunic (left), the bulla around his neck and the trousers.

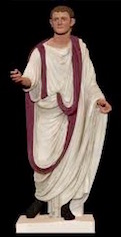

When the boy grew older, he wore the toga praetexta as a symbol that he was approaching manhood.

Between the ages of 14-17, a Roman boy became a man and a citizen of Rome. At that time he began to wear the toga virilis, meaning “toga of manhood.”

When the young man assumed the toga virilis, his father sent him for a year to a friend or mentor in the army or in civilian life. There he began his training to be a useful and patriotic Roman citizen.

The young girls were married off at early ages between 14 and 18. Notice the wary looks on both the face of the bride and the groom (below). It probably was an arranged marriage. The marriage contract is in the hands of the woman between the two young people. Both young people are clad in beautiful, likely colorful, togas. The young woman has a head scarf that could have hid her face before the marriage ceremony.

When girls were young, their mother taught them the Roman virtues and the arts of home management, weaving, sewing and if she was a normal citizen and did not have servants, the art of cooking.

In the years of the Roman Republic (509-27 BC) Roman women were the glue that held the Republic together because they held the home together. Roman men conquered the world. Roman women raised those Roman men. There is praise for the girls and the women of the Roman Republic. And there is more praise for the women who are clothed with the righteousness in Proverbs 31:10-31 and raise virtuous and Godly children.— Sandra Sweeny Silver

In the years of the Roman Republic (509-27 BC) Roman women were the glue that held the Republic together because they held the home together. Roman men conquered the world. Roman women raised those Roman men. There is praise for the girls and the women of the Roman Republic. And there is more praise for the women who are clothed with the righteousness in Proverbs 31:10-31 and raise virtuous and Godly children.— Sandra Sweeny Silver