Since both men and women have two legs, it would seem logical that clothes for the lower body as well as underwear would be two-legged. But that was not the norm in the ancient western world of Egypt, Greece and Rome. Flowing long togas and mid-thigh one-piece tunics were the general dress of both men and women in the Roman world of the ancient Christians in the first centuries AD. [CLICK HERE for article on togas and tunics.]

The whole ancient world, however, was not flowing in robes. In May 2014 two pairs of 3,300 year-old animal-skin trousers were found on two mummies in Xinjang region of China (left).

It is hypothesized that these trousers were worn by very ancient shamans who were considered religious leaders and wore that distinctive clothing. But because of the colder weather in China rather than in Egypt, Greece or Rome, it is more than logical that trousers were the norm for ancient Chinese, their shamans and all those in colder climes. Roman soldiers who subdued Gaul (France and environs) under Julius Caesar in 58-50 BC adopted trousers like the Gauls wore called bracae. When, however, they returned to Rome after 8 years, they reverted back to tunics/togas.

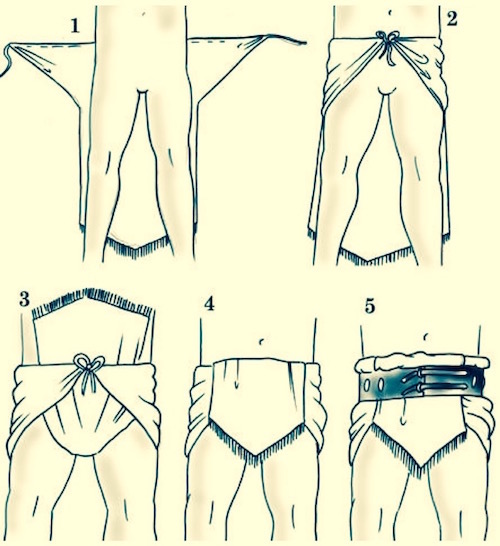

Under the toga or tunic the typical Roman man or woman would wear a loincloth, an undergarment called a subligaculum, meaning “tied on under.” The loincloth was, like the toga, just a piece of cloth, usually linen, that required intricate folding. A woman would put on her tunic or toga over the subligaculum. As can be seen below, a man could just wear the loincloth if it had fringes or a leather belt buckled over the top of the loincloth.

As can be seen from the mosaic below, many classes of Romans wore no undergarment at all.

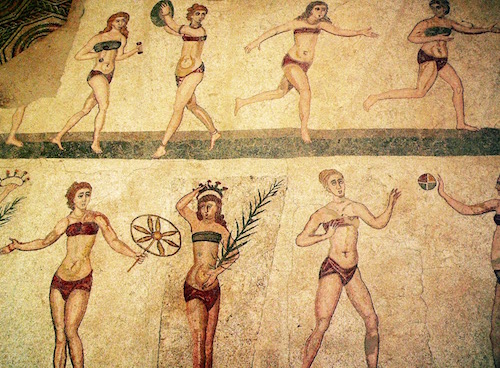

There are, also, mosaics and paintings of women in what looks like a two-piece bathing suit. The women below seem to be dancers, musicians or professional entertainers hired for certain events. One is playing a cymbal and the other has bells.

The painting below (from a bedroom at Villa Romana del Casale in Piazz Amerina del Casale, Sicily) shows women participating in athletic contests. One is racing. Two others are playing a ball game with a leather ball (America and rubber would be discovered about 1,500 years later). When women participated in sports, they wore strapless bras and underpants similar to ours today.

Clearly there were winners and losers in sports just like today. The togaed woman on the left (below) is running to give the center woman her crown and her victory wreath. The woman on the right has already received her crown and victor’s wreath.

It is assumed that the “sports bra” worn by these women athletes was similar to the strophium, also called a mamillare, a tight bra worn under the togas/tunics of women of the time. Apparently large breasts were considered “grandmotherly” in the ancient world and, unlike our culture, were body parts which should be hidden and bound tightly.

Martial in his Epigrams emphasizes this view: “Afra talks of her papas and her mammas; but she herself may be called the grandmamma of her papas and mammas.” Epigrams 1.100

If the brassiere band was tightly tied across the bust and outside the toga, it was called a fascia, a Latin word derived from fasces, meaning “a tight bundle.” It is always interesting to look up the etymology of a word in Latin or English or Chinese.

In one way or another in the civilized world men and women have had to contend with outerwear and underwear. Outerwear has always had a fascination and has had many styles and many fabrics and many designs over the millennia. Underwear, on the other hand, is just the basic covering of genitals and breasts. So sporting wear for women in the ancient Roman world does not look so different from underwear in our world. And it is not beyond reason that many Christian and Roman women wore panties and bras that look like the ones we’ve seen. For modern men the loincloth is definitely more complicated in its intricate folding than putting on boxers or briefs.

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), the German playwright and director, saw the quotidian importance of underwear from the cradle to the grave.—Sandra Sweeny Silver