If the Roman writer Suetonius had not written and published his Lives of the Twelve Caesars in 121 AD, we would know much less about the famous Roman games and entertainments in the Circus in ancient Rome and about the lives of each of the first twelve Caesars. His book chronicles the family history of each of the first twelve Emperors of Rome, a description of his appearance, his eccentricities, his daily routines, quotes from him, victories and defeats in battles and, for the purpose of this article, the type of games and gladiatorial fights he gave to the ever eager Roman people. The writer enthusiastically recommends Suetonius’ fascinating book. It is because Suetonius is so full of information that this article will quote exclusively from his book. CLICK FOR BOOK

We begin with Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) who was declared Dictator For Life (Dictator In Perpetuum) on January 28, 44 BC.

We begin with Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) who was declared Dictator For Life (Dictator In Perpetuum) on January 28, 44 BC.

His sole dictatorship paved the way for the Emperors who ruled by fiat, were declared gods and would be during their reign total dictators of the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar was assassinated several months after that declaration on the Ides of March, March 15, 44 BC:

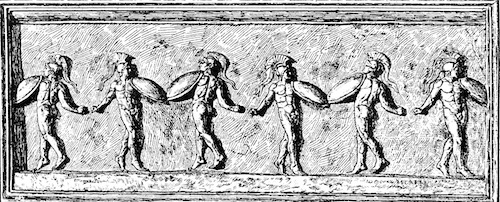

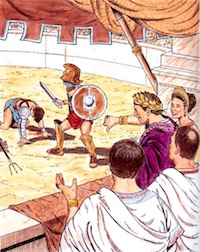

“(Julius Caesar) gave entertainments of divers kinds: a combat of gladiators and also stage-plays in every ward all over the city, performed too by actors of all languages, as well as races in the circus, athletic contests, and a sham sea-fight. In the gladiatorial contest in the Forum Furius Leptinus, a man of praetorian stock, and Quintus Calpenus, a former senator and pleader at the bar, fought to a finish. A Pyrrhic dance (a war-themed ballet) was performed by the sons of the princes of Asia and Bithynia (royalty was often imported to Rome to perform this dance).

During the plays Decimus Laberius, a Roman knight, acted a farce of his own composition, and having been presented with five hundred thousand sesterces and a gold ring, (Laberius had forfeited that amount of money in order to appear in the circus and it was restored to him after his performance) passed from the stage through the orchestra and took his place in the fourteen rows (the first fourteen rows above the orchestra were reserved for the knights by the law of L. Roscius Otho, tribune of the commons, 67 B.C.).

For the (chariot) races the circus was lengthened at either end and a broad canal was dug all about it; then young men of the highest rank drove four-horse and two-horse chariots and rode pairs of horses, vaulting from one to the other. The game called Troy was performed by two troops, of younger and of older boys.(The game of Troy was an equestrian event where teenagers, too young to be in the army, wove in labyrinthine ways in and out of maneuvers.)

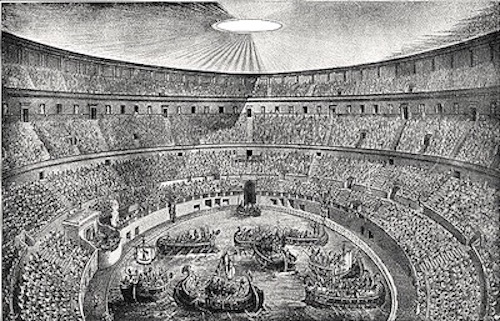

Combats with wild beasts were presented on five successive days, and last of all there was a battle between two opposing armies, in which five hundred foot-soldiers, twenty elephants, and thirty horsemen engaged on each side. To make room for this, the goals were taken down and in their place two camps were pitched over against each other. The athletic competitions lasted for three days in a temporary stadium built for the purpose in the region of the Campus Martius. For the naval battle a pool was dug in the lesser Codeta and there was a contest of ships of two, three, and four banks of oars, belonging to the Tyrian and Egyptian fleets, manned by a large force of fighting men.

Such a throng flocked to all these shows from every quarter, that many strangers had to lodge in tents pitched in streets or along the roads, and the press was often such that many were crushed to death, including two senators.” Suetonius, Lives Of The Twelve Caesars: Life of Julius Caesar 39

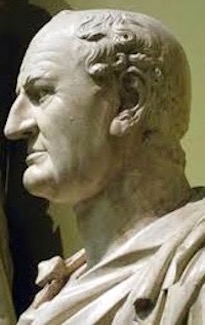

Augustus Caesar, 63 BC—14 AD (right), is considered the first of the Roman Emperors even though Suetonius included Julius Caesar who had paved the way for the dictatorships to follow.

Augustus Caesar, 63 BC—14 AD (right), is considered the first of the Roman Emperors even though Suetonius included Julius Caesar who had paved the way for the dictatorships to follow.

“(Augustus Caesar) surpassed all his predecessors in the frequency, variety, and magnificence of his public shows. He says that he gave games four times in his own name and twenty-three times for other magistrates, who were either away from Rome or lacked means. He gave them sometimes in all the wards and on many stages with actors in all languages, and combats of gladiators not only in the Forum or the amphitheater, but in the Circus….Sometimes, however, he gave nothing except a fight with wild beasts.

He gave athletic contests too in the Campus Martius, erecting wooden seats; also a sea-fight, constructing an artificial lake near the Tiber, where the grove of the Caesars now stands…. In the Circus he exhibited charioteers, runners, and slayers of wild animals, who were sometimes young men of the highest rank. Besides he gave frequent performances of the game of Troy by older and younger boys, thinking it a time-honored and worthy custom for the flower of the nobility to become known in this way. When Nonius Asprenas was lamed by a fall while taking part in this game (of Troy), he presented him with a golden necklace and allowed him and his descendants to bear the surname Torquatus. But soon after he gave up that form of entertainment, because Asinius Pollio the orator complained bitterly and angrily in the senate of an accident to his grandson Aeserninus, who also had broken his leg.

(Augustus) sometimes employed even Roman knights in scenic and gladiatorial performances, but only before it was forbidden by decree of the senate (who thought it below their ranks to participate in the games).

After that he exhibited no one of respectable parentage, with the exception of a young man named Lycius, whom he showed merely as a curiosity; for he was less than two feet tall, weighed but seventeen pounds, yet had a stentorian voice.

CLICK HERE for article on Boxing in Ancient Rome

(Augustus) did however on the day of one of the shows make a display of the first Parthian hostages (from modern-day Iran and Iraq) that had ever been sent to Rome, by leading them through the middle of the arena and placing them in the second row above his own seat. Furthermore, if anything rare and worth seeing was ever brought to the city, it was his habit to make a special exhibit of it in any convenient place on days when no shows were appointed. For example a rhinoceros in the Saepta, a tiger on the stage and a snake of fifty cubits (75 feet) in front of the Comitium.

It chanced that at the time of the games which he had vowed to give in the circus, he was taken ill and headed the sacred procession lying in a litter; again, at the opening of the games with which he dedicated the theatre of Marcellus, it happened that the joints of his curule chair gave way and he fell on his back.

At the games for his grandsons, when the people were in a panic for fear the theatre should fall, and he could not calm them or encourage them in any way, he left his own place and took his seat in the part which appeared most dangerous. He himself usually watched the games in the Circus from the upper rooms of his friends and freedmen but sometimes from the imperial box and even in company with his wife and children.

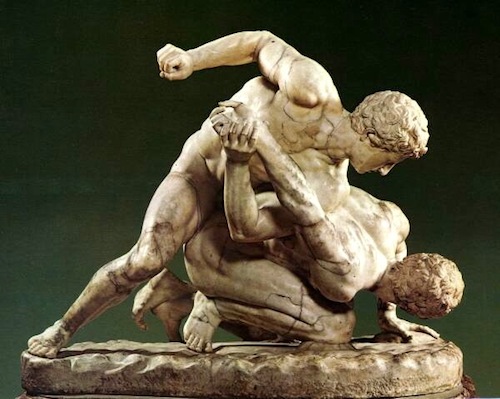

He was sometimes absent for several hours, and now and then for whole days, making his excuses and appointing presiding officers to take his place. But whenever he was present, he gave his entire attention to the performance….he used to offer special prizes and numerous valuable gifts from his own purse at games given by others….He was especially given to watching boxers, particularly those of Latin birth, not merely such as were recognized and classed as professionals, whom he was wont to match even with Greeks, but the common untrained townspeople that fought rough and tumble and without skill in the narrow streets.

In fine, he followed with his interest all classes of performers who took part in the public shows; maintained the privileges of the athletes and even increased them; forbade the matching of gladiators without the right of appeal for quarter; and deprived the magistrates of the power allowed them by an ancient law of punishing actors anywhere and everywhere, restricting it to the time of games and to the theatre.

Nevertheless he exacted the severest discipline in the contests in the wrestling halls and the combats of the gladiators. In particular he was so strict in curbing the lawlessness of the actors that when he learned that Stephanio, an actor of Roman plays, was waited on by a matron with hair cut short to look like a boy, he had him whipped with rods through the three theaters and then banished him. Hylas, a pantomimic actor, was publicly scourged in the atrium of his own house, on complaint of a praetor, and Pylades was expelled from the city and from Italy as well, because by pointing at him with his finger (that is, his middle finger, infamis digitus, it implied a charge of obscenity, and still does today) he turned all eyes upon a spectator who was hissing him.” Suetonius, Lives Of The Twelve Caesars: Life of Augustus 43

“(Caligula) gave several gladiatorial shows, some in the amphitheater of Taurus and some in the Saepta, in which he introduced pairs of African and Campanian boxers, the pick of both regions.

He did not always preside at the games in person, but sometimes assigned the honor to the magistrates or to friends. He exhibited stage-plays continually, of various kinds and in many different places, sometimes even by night, lighting up the city.

He also threw about gifts of various kinds, and gave each man a basket of victuals. During the feasting he sent his share to a Roman knight opposite him, who was eating with evident relish and appetite, while to a senator for the same reason he gave a commission naming him praetor out of the regular order. He also gave many games in the Circus, lasting from early morning until evening, introducing between the races now a baiting of panthers and now the maneuvers of the game called Troy; some, too, of special splendor, in which the Circus was strewn with red and green, while the charioteers were all men of senatorial rank.

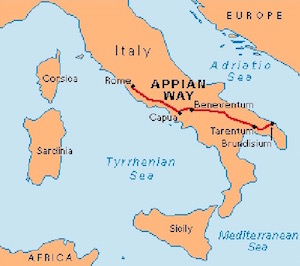

He also started some games off-hand, when a few people called for them from the neighboring balconies, as he was inspecting the outfit of the Circus. Besides this, he devised a novel and unheard of kind of pageant; for he bridged the gap between Baiae and the mole at Puteoli, a distance of about thirty-six hundred paces (3 and a half Roman miles) by bringing together merchant ships from all sides and anchoring them in a double line, afterwards a mound of earth was heaped upon them and fashioned in the manner of the Appian Way.

Over this bridge he rode back and forth for two successive days, the first day on a caparisoned (richly adorned) horse, himself resplendent in a crown of oak leaves, a buckler, a sword, and a cloak of cloth of gold; on the second, in the dress of a charioteer in a car drawn by a pair of famous horses, carrying before him a boy named Dareus, one of the hostages from Parthia, and attended by the entire praetorian guard and a company of his friends in Gallic chariots. I know that many have supposed that Gaius devised this kind of bridge in rivalry of Xerxes (Persian king 519—466 BC), who excited no little admiration by bridging the much narrower Hellespont; others, that it was to inspire fear in Germany and Britain, on which he had designs, by the fame of some stupendous work.

Over this bridge he rode back and forth for two successive days, the first day on a caparisoned (richly adorned) horse, himself resplendent in a crown of oak leaves, a buckler, a sword, and a cloak of cloth of gold; on the second, in the dress of a charioteer in a car drawn by a pair of famous horses, carrying before him a boy named Dareus, one of the hostages from Parthia, and attended by the entire praetorian guard and a company of his friends in Gallic chariots. I know that many have supposed that Gaius devised this kind of bridge in rivalry of Xerxes (Persian king 519—466 BC), who excited no little admiration by bridging the much narrower Hellespont; others, that it was to inspire fear in Germany and Britain, on which he had designs, by the fame of some stupendous work.

But when I (Suetonius) was a boy, I used to hear my grandfather say that the reason for the work, as revealed by the emperor’s confidential courtiers, was that Thrasyllus the astrologer (left—born? died 36 AD) had declared to Tiberius, when he was worried about his successor and inclined towards his natural grandson (Tiberius Gemellus son of his dead son Drusus) that Gaius had no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding about over the gulf of Baiae with horses (Caligula had Tiberius’ heir Gemellus murdered and he succeeded to power in 37 which he maniacally held until his assassination in 41 AD) .

But when I (Suetonius) was a boy, I used to hear my grandfather say that the reason for the work, as revealed by the emperor’s confidential courtiers, was that Thrasyllus the astrologer (left—born? died 36 AD) had declared to Tiberius, when he was worried about his successor and inclined towards his natural grandson (Tiberius Gemellus son of his dead son Drusus) that Gaius had no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding about over the gulf of Baiae with horses (Caligula had Tiberius’ heir Gemellus murdered and he succeeded to power in 37 which he maniacally held until his assassination in 41 AD) .

He also gave shows in foreign lands, Athenian games at Syracuse in Sicily, and miscellaneous games at Lugdunum in Gaul; at the latter place also a contest in Greek and Latin oratory, in which, they say, the losers gave prizes to the victors and were forced to compose eulogies upon them, while those who were least successful were ordered to erase their writings with a sponge or with their tongue unless they elected rather to be beaten with rods or thrown into the neighboring river.” Suetonius, Lives Of The Twelve Caesars: The Life Of Caligula 18-20

The above is a foretaste of a few of the fascinating aspects of the lives of the Caesars and the games they enjoyed and sponsored. These games were performed, also, concurrent with the rise of the Christian religion and many Christians were martyred during those “games.”. The following assessment of the Roman games to which Tertullian, the Father of Western Theology, was once so addicted before his conversion to Christianity is from Tertullian’s post-conversion book De Spectaculis:

“What, then, you say; shall I be in danger of pollution if I go to the circus when the games are not being celebrated? There is no law forbidding the mere places to us. For not only the places for show-gatherings, but even the temples, may be entered without any peril of his religion by the servant of God, if he has only some honest reason for it…. Why, even the streets and the market-place, and the baths, and the taverns, and our very dwelling-places, are not altogether free from idols.

Satan and his (demons) have filled the whole world. It is not by merely being in the world, however, that we lapse from God, but by touching and tainting ourselves with the world’s sins. I shall break with my Maker, that is, by going to the Capitol or the temple of Serapis to sacrifice or adore, as I shall also do by going as a spectator to the circus and the theatre. The places in themselves do not contaminate, but what is done in them….The polluted things pollute us.”—Article by Sandra Sweeny Silver