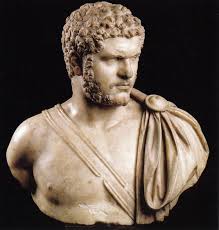

In Ankara, the capital of Turkey, are the ruins of a Roman bath built by Emperor Caracalla and dedicated to Asclepios, the god of healing.

Ankara, then known as Ancyra, was the capital city of Galatia, an ancient area in Asia Minor principally known today for its association with the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Galatians (c. 48-52) in the New Testament. Galatia had been conquered by Caesar Augustus and annexed to Rome in 25 BC. Two bronze tablets inscribed with Augustus’ The Deeds have been found in the ruins of his temple in Ankara.

CLICK HERE for article on the deeds of Augustus

In order to maintain the Roman Peace, the Pax Romana, Augustus settled soldiers and their families in all conquered cities and regions. Over time thousands of Romans were living in the Galatian area and they wanted the hallmark of their culture—a Roman Bath. In 212 Emperor Caracalla built them their bath.

In that same year Caracalla (aka Antononius) had issued a decree, the Constitutio Antoniana, declaring that all free men in the entire Empire were Roman citizens and all free women had the same rights as Roman women. This declaration vastly increased the number of people who would pay taxes to Rome, took away ambivalent identity (“Am I a Gaul or a Roman?”) and gave Caracalla much more money to build baths.

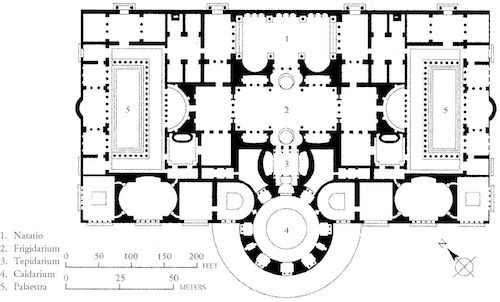

The Bath in Ancyra, a symbol of Rome and of the Galatians’ new Roman citizenship, was large. The main hall was 262’ wide and 427’ long. Off the main hall were auxiliary buildings. In the buildings were hot pools, warm pools, a swimming pool, recreation facilities and rooms for cultural events. The ancient Turks loved this bath so much that the modern-day Turkish people with their famous Turkish baths are the only people in the world who have for thousands of years maintained a direct historical link to the fabled Roman Baths.

In 212 Caracalla, also, began to build in Rome the most famous of all the Baths, the Baths of Caracalla. Covering over 33 acres, it was the second largest Roman Imperial Bath, exceeded in size only by the Baths of Diocletian dedicated 100 years later in 306. Caracalla built his Baths, called in Latin thermae (“warm springs”), near Aventine Hill close to the Via Appia, the main road of entry into Rome, where every visitor could see and be impressed with his massive, multi-billion sesterces homage to the art of bathing.

The water to supply his Baths was diverted from the largest of Rome’s eleven aqueducts, the Aqua Marcia that carried into Rome the cool and sweet waters of the Aniene River 57 miles away.

The water for the Baths was stored on the premises in a double row of 64 cisterns behind the seats of a stadium near one of the two rectangular buildings (palaestrae) where athletes practiced and competed in sporting events. Special athletic events were staged in the Bath’s stadium. It had only one bank of tiered seats. The rest of the stadium was left open so people who were exercising or strolling could see the contests.

13,000 recently captured Scottish slaves had leveled the land for the Bath. 21 million bricks faced the outside of the buildings. 600 marble workers from Greece were employed to carve the 6,400 square yards of marble and granite columns, facings, friezes, entablatures and statuary that adorned the inside rooms and courtyards.

Caracalla spared no expense for the stones and marbles inside his Bath. He imported grey granite from Egypt, yellow marble from Numidia, a green-veined marble from the island of Carystus in the Mediterranean, green porphyry from Sparta and the prized purple porphyry from a quarry in Egypt. Purple was the color of royalty and the royal Emperor Constantine the Great’s casket was made of this purple porphyry. The porphyry from that one quarry in Egypt was very expensive and rare. Its fame was so great that even to this day, the road from that quarry to an ancient city on the Nile is called The Porphyry Road (Via Porphyrites).

Bathing was usually done in the afternoon because the Roman citizen’s workday was typically over at midday. The beating of a great copper gong announced the opening of all the Baths. The Roman orator and philosopher Cicero said the sound of that gong was for him “sweeter than the voices of all the philosophers in Athens.”

The central building of the Baths of Caracalla was a gigantic 253,000 square feet. The Baths could hold 1,600 bathers not counting the hundreds of other people who came just for social or business reasons. Sometimes the baths were free, but usually there was a small fee paid at one of the four entrances. The main entrance was on the northeast where the cloak and changing rooms (apodyterium) were. To show they were socially prominent, patrician men and women often brought a large contingent of slaves with them.

Slaves carried all the paraphernalia needed for an afternoon at the Baths: linen towels, exercise and bathing clothes, boxes for jewelry and other sundry items, dishes for scooping water, a toilet kit containing flasks of perfumed oils (top left), olive oil as soap (the very poor used lentil flour as soap) and a curved tool made of metal or bone called a “strigil” used for scraping off dirt (bottom left), water and oil.

Slaves carried all the paraphernalia needed for an afternoon at the Baths: linen towels, exercise and bathing clothes, boxes for jewelry and other sundry items, dishes for scooping water, a toilet kit containing flasks of perfumed oils (top left), olive oil as soap (the very poor used lentil flour as soap) and a curved tool made of metal or bone called a “strigil” used for scraping off dirt (bottom left), water and oil.

Caracalla’s Bath in Rome has impacted the architecture of many buildings. Emperor Diocletian (reigned from 284 to 305) imitated his frigidarium, the central part of the Bath. In the early 1900’s the main halls of New York City’s Penn Station (demolished in 1963) and the Chicago Union Station were designed directly from the frigidarium area in Caracalla’s Bath.

Penn Station was opened on September 8, 1910 to the wonder of the entire word. It was torn down and rebuilt between 1963 and 1966. No one was or is amazed at the current Penn Station. Many mourn the loss of that magnificent, now gone, original, Caracallian-like architectural masterpiece.

As Vincent Scully (1920-2017), art historian from Yale, once said, “Through Pennsylvania Station one entered the city like a god. Perhaps it was really too much. One scuttles in now like a rat.”—Article by Sandra Sweeny Silver