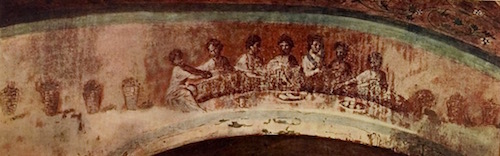

The Fractio Panis fresco, early 100’s, is the clearest example we have in catacomb art of the ritual of the Eucharist in the first two hundred years of the Gentile Church in Rome. In the New Testament book of Acts (c. 63-70) there are references to Christians gathering to “break bread,” called an “Agape Love Feast.”

“They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer.” Acts 2:42 “They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts.” Acts 2:46

The catacombs in Rome contain many frescos telling us what those Christians living between c.100–c.350 AD believed, how they lived out that faith and what things were most important to their faith. The Fractio Panis (Latin meaning “Breaking of Bread”) fresco in the Catacomb of Priscilla on the Via Salaria is liturgically and theologically one of the most famous of catacomb paintings because it gives an idea of how they took Communion, the Eucharist.

Seven people, one of whom is a woman, are reclined/seated at a table where there is a cup of mingled red wine and two large plates. One plate contains five loaves of bread, the other two fish, replicating the numbers in the multiplication miracle from the Gospels. A man (presbyter/priest?) at the left end of the table has a small loaf in his hands. His arms are stretched out in front of him to show he is breaking the bread as Jesus broke the bread at the Last Supper and before He fed the five thousand and the four thousand. Near the man is a two-handled cup. On one side of the painting are four wicker baskets overflowing with bread. On the other side there are three baskets filled with bread representing the “seven basketfuls of broken pieces that were left over” (Mt. 15:37) after Jesus had fed the four thousand.

The Fractio Panis fresco illuminates more clearly how the early catacomb Christians celebrated the Lord’s Supper. We see the Eucharist bread is broken and blessed by the laying on of hands. A cup of wine is present as are two fish. All three elements are on the table. Two millennia later Christian Communion is exclusively celebrated (Latin celebrare meaning “to assemble to honor”) as reflecting the Last Supper when Jesus pronounced the Bread His Body and the Wine His Blood. According to their iconography, the catacomb Christians gave the Eucharist a much broader context by including fish in the ritual.

CLICK FOR ARTICLE ON ICHTHUS SYMBOL

There is a very early description of the correct way to celebrate the Eucharist (meaning in Greek “thanksgiving”) in the Didache, a work cited by the Christian writers Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215), Eusebius of Caesarea (263-339) and Athanasius (c. 293-373). Though known through those authors, the Didache in manuscript form had been lost for over 1,400 years until it was re-discovered in 1873 by a Greek Orthodox Metropolitan, Philotheos Bryennios, in the Jerusalem Monastery of the Most Holy Sepulcher in Istanbul.

Bryennios published the Didache in 1883. It was immediately recognized as one of the most important manuscripts (Latin manu meaning “by hand” and scriptus meaning “written”) of the Early Church because it was obviously written before church hierarchy was firmly in place and was very close to the Jewish Apostolic Age.

The Didache begins: “The teaching of the Lord through the twelve Apostles to the Gentiles ( meaning ‘nations’).”

According to the Teaching, this is how the Eucharist should be celebrated:

“And with respect to the thanksgiving meal, you shall give thanks as follows: First with respect to the cup: ‘We give you thanks, our Father, for the holy vine of David, your child, which you made known to us through Jesus your child. To you be the glory forever.’

And with respect to the fragment of bread: ‘We give you thanks, our Father, for the life and knowledge that you made known to us through Jesus your child. To you be the glory forever.

As this fragment of bread was scattered upon the mountains and was gathered to become one, so may your church be gathered together from the ends of the earth into your kingdom. For the glory and the power are yours through Jesus Christ forever.’

But let no one eat or drink from your thanksgiving meal unless they have been baptized in the name of the Lord. For also the Lord has said about this, ‘Do not give what is holy to the dogs.’

And when you have had enough to eat, you shall give thanks as follows: ‘We give you thanks, holy Father, for your holy name which you have made reside in our hearts, and for the knowledge, faith and immortality that you made known to us through Jesus your child. To you be the glory forever.

You, O Master Almighty, created all things for the sake of your name, and gave both food and drink to humans for their refreshment, that they might give you thanks. And you graciously provided us with spiritual food and drink and eternal life through your child.

Above all we thank you because you are powerful. To you be the glory forever. Remember your church, O Lord; save it from all evil, and perfect it in your love. And gather it from the four winds into your kingdom, which you prepared for it. For yours is the power and the glory forever.

May grace come and this world pass away. Hosanna to the God of David. If anyone is holy, let him come; if any one is not, let him repent. Maranatha! (Come, Lord!) Amen. (So be it.)

But permit the prophets to give thanks (or: ‘hold the eucharist’) as often as they wish.’” Didache 9. 10

Several centuries later the 4th century Gentile theologian Cyril of Jerusalem left a more detailed and ritualistic instruction for Communion ((Latin communionem meaning “fellowship/sharing”). While the Didache concentrates on prayer and thanksgiving, Cyril’s instructions emphasize technique:

“Approaching (Communion)…come not with your palms extended and stretched flat nor with your fingers open. But make your left hand as if a throne for the right, and hollowing your palm receive the body of Christ saying after it, Amen. Then after you have with care sanctified your eyes by the touch of the holy Body, partake…giving heed lest you lose any particle of it (the bread). For should you lose any of it, it is as though you have lost a member of your own body, for tell me, if any one gave you gold dust, would you not with all precaution keep it fast, being on the guard lest you lose any of it and thus suffer loss? How much more cautiously then will you observe that not a crumb falls from you, of what is more precious than gold and precious stones. Then having partaken of the Body of Christ, approach also the cup of His blood; not extending your hands, but bending low and saying in the way of worship and reverence, Amen, be you sanctified by partaking, also of the blood of Christ.” Catechetical Lecture 5

The celebration of the Lord’s Supper was for the early Christians an extremely solemn occasion. Cyril describes the Bread/Body as more precious than gold or costly gems and admonishes them not to let a crumb of it fall to the ground. At the time of Cyril of Jerusalem, a 12-year-old boy in Rome, Tarcisius, was charged with carrying the consecrated bread down the street to some shut-ins. The Spanish Pope Damasus (c. 304-384) has inscribed what happened:

“When a wicked group of young fanatics flung themselves on Tarcisius who was carrying the Eucharist, not wanting to profane the sacrament, thereby preferred to give his life rather than yield up The Body of Christ to the rabid dogs.”

The holy boy, Tarcisius, is called “the Eucharist martyr.” He was beaten to death rather than let the Communion bread fall on the ground. He is buried in the Catacomb of Callixtus where the poem of Damasus honors his sacrifice.

One thing is sure. The early Christians reverently and reflectively celebrated the Eucharist with bread and wine. But it is moot whether they ate the fish with the sacrament or included the fish as symbol of the totality of the bread and wine, Christ’s Body, Ichthus. Perhaps the fish depicted on Communion tables in the catacombs has a meaning yet to be comprehended by modern Christians.—By Sandra Sweeny Silver