Ancient Accounts Of The Assassination Of Julius Caesar: On The Ides (15th) March 44 BC

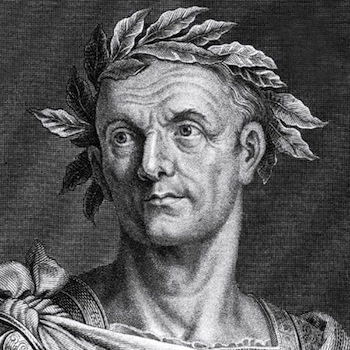

Suetonius (70-130 AD) gives the only physical description of Caesar: “He was tall, of a fair complexion, round limbed, rather full faced, with eyes black and piercing….kept the hair of his head closely cut and had his face smoothly shaved. His baldness gave him much uneasiness…he used to brush forward the hair from the crown of his head, and of all the honors conferred on him by the Senate and People, there was none which he either accepted or used with greater pleasure than the right of constantly wearing a laurel crown.” Lives Of The Caesars: Julius Caesar 45

Julius Caesar had declared himself “dictator for life” in 45 BC. Those who opposed Rome having a monarch and wanted Rome to return to a Republic were called Liberators and began plotting Caesar’s death. On the night before Julius Caesar’s assassination, his wife dreamed that the foundation of their house fell down and her husband was stabbed in her arms. Caesar was not feeling very well the next day and decided not to go to the Senate, but Brutus, one of the conspirators, urged him to go. He left for the Senate about 11:00 in the morning. Julius had been warned by the soothsayer Spurinna to “Beware the Ides of March.” When he was on his way to the Senate that morning, he passed the seer and said, “This is the Ides of March.” Spurinna replied, “Yes, but it has not passed.”

Cassius Dio in his History 16-19 written in c. 211 AD writes;

“It had been decided by them (the c. 40 conspirators who wanted to return Rome to a Republic after Caesar had declared himself Dictator For Life) to make the attempt in the senate, for they thought that there Caesar would least expect to be harmed in any way and would thus fall an easier victim, while they would find a safe opportunity by having swords instead of documents brought into the chamber in boxes, and the rest, being unarmed, would not be able to offer any resistance. But in case any one should be so rash, they hoped at least that the gladiators, many of whom they had previously stationed in Pompey’s Theater under the pretext that they were to contend there, would come to their aid; for these were to lie in wait somewhere there in a certain room of the peristyle. So the conspirators, when the appointed day was come, gathered in the senate-house at dawn and called for Caesar. As for him, he was warned of the plot in advance by soothsayers, and was warned also by dreams.

For the night before he was slain his wife dreamed that their house had fallen in ruins and that her husband had been wounded by some men and had taken refuge in her bosom; and Caesar dreamed he was raised aloft upon the clouds and grasped the hand of Jupiter. Moreover, omens not a few and not without significance came to him: the arms of Mars, at that time deposited in his house, according to ancient custom, by virtue of his position as high priest, made a great noise at night, and the doors of the chamber where he slept opened of their own accord. Moreover, the sacrifices which he offered because of these occurrences were not at all favorable, and the birds he used in divination forbade him to leave the house. Indeed, to some the incident of his golden chair seemed ominous, at least after his murder; for the attendant, when Caesar delayed his coming, had carried it out of the senate, thinking that there now would be no need of it.

Caesar, accordingly, was so long in coming that the conspirators feared there might be a postponement, — indeed, a rumor got abroad that he would remain at home that day, — and that their plot would thus fall through and they themselves would be detected.

Therefore they sent Decimus Brutus, as one supposed to be his devoted friend, to secure his attendance. This man made light of Caesar’s scruples and by stating that the senate desired exceedingly to see him, persuaded him to proceed. At this an image of him, which he had set up in the vestibule, fell of its own accord and was shattered in pieces. But, since it was fated that he should die at that time, he not only paid no attention to this but would not even listen to some one who was offering him information of the plot. He received from him a little roll in which all the preparations made for the attack were accurately recorded, but did not read it, thinking it contained some indifferent matter of no pressing importance. In brief, he was so confident that to the soothsayer who had once warned him to beware of that day he jestingly remarked: “Where are your prophecies now? Do you not see that the day which you feared is come and that I am alive?’ And the other, they say, answered merely: ‘Ay, it is come but is not yet past.’

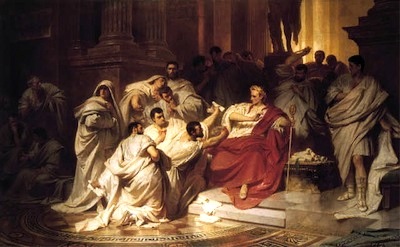

Now when he finally reached the senate, Trebonius kept Antony employed somewhere at a distance outside. For, though they had planned to kill both him and Lepidus, they feared they might be maligned as a result of the number they destroyed, on the ground that they had slain Caesar to gain supreme power and not to set free the city, as they pretended; and therefore they did not wish Antony even to be present at the slaying. As for Lepidus, he had set out on a campaign and was in the suburbs. When Trebonius, then talked with Antony, the rest in a body surrounded Caesar, who was as easy of access and as affable as any one could be; and some conversed with him, while others made as if to present petitions to him, so that suspicion might be as far from his mind as possible.

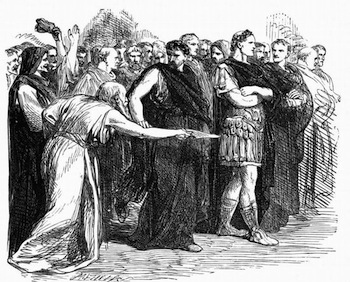

And when the right moment came, one of them approached him, as if to express his thanks for some favor or other, and pulled his toga from his shoulder, thus giving the signal that had been agreed upon by the conspirators.

Thereupon they attacked him from many sides at once and wounded him to death, so that by reason of their numbers Caesar was unable to say or do anything, but veiling his face, was slain with many wounds (he had 23 stab wounds). This is the truest account, though some have added that to Brutus, when he struck him a powerful blow, he said: “Thou, too, my son?’”

Writing c. 110 A.D., Plutarch in Lives: Life of Brutus 5 explains why Caesar may have considered Brutus his son:

“And this he (Caesar) is believed to have done out of a tenderness to Servilia, the mother of Brutus; for Caesar had, it seems, in his youth been very intimate with her, and she passionately in love with him; and, considering that Brutus was born about that time in which their loves were at the highest, Caesar had a belief that he was his own child. The story is told, that when the great question of the conspiracy of Catiline, which had like to have been the destruction of the commonwealth, was debated in the senate, Cato and Caesar were both standing up, contending together on the decision to be come to; at which time a little note was delivered to Caesar from without, which he took and read silently to himself. Upon this, Cato cried out aloud, and accused Caesar of holding correspondence with and receiving letters from the enemies of the commonwealth; and when many other senators exclaimed against it, Caesar delivered the note as he had received it to Cato, who reading it found it to be a love-letter from his own sister Servilia, and threw it back again to Caesar with the words, “Keep it, you drunkard,” (Julius Caesar was a moderate drinker) and returned to the subject of the debate. So public and notorious was Servilia’s love to Caesar.”

If one compares the busts of a young Brutus and a young Caesar, there is a resemblance (see below).

Another ancient account of the assassination of Julius Caesar is in Suetonius’, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Julius Caesar 80-82 written c. 121 AD:

“More than sixty joined the conspiracy against him, led by Gaius Cassius and Marcus and Decimus Brutus. At first they hesitated whether to form two divisions at the elections in the Campus Martius, so that while some hurled him from the bridge as he summoned the tribes to vote, the rest might wait below and slay him; or to set upon him in the Sacred Way or at the entrance to the theatre. When, however, a meeting of the Senate was called for the Ides of March in the Hall of Pompey, they readily gave that time and place the preference…. Now Caesar’s approaching murder was foretold to him by unmistakable signs. A few months before, when the settlers assigned to the colony at Capua by the Julian Law were demolishing some tombs of great antiquity, to build country houses, and plied their work with the greater vigor because as they rummaged about they found a quantity of vases of ancient workmanship, there was discovered in a tomb, which was said to be that of Capys, the founder of Capua, a bronze tablet, inscribed with Greek words and characters to this purport: “Whenever the bones of Capys shall be moved, it will come to pass that a son of Ilium shall be slain at the hands of his kindred, and presently avenged at heavy cost to Italy.” And let no one think this tale a myth or a lie, for it is vouched for by Cornelius Balbus, an intimate friend of Caesar. Shortly before his death, as he was told, the herds of horses which he had dedicated to the river Rubicon when he crossed it (January 49 BC), and had let loose without a keeper, stubbornly refused to graze and wept copiously.

The Lives of the Twelve Caesars

Again, when he was offering sacrifice, the soothsayer Spurinna warned him to beware of danger, which would come not later than the Ides of March; and on the day before the Ides of that month a little bird called the king-bird flew into the Hall of Pompey with a sprig of laurel, pursued by others of various kinds from the grove hard by, which tore it to pieces in the hall. In fact the very night before his murder he dreamt now that he was flying above the clouds, and now that he was clasping the hand of Jupiter; and his wife Calpurnia thought that the pediment of their house fell, and that her husband was stabbed in her arms; and on a sudden the door of the room flew open of its own accord.

Both for these reasons and because of poor health he hesitated for a long time whether to stay at home and put off what he had planned to do in the senate; but at last, urged by Decimus Brutus not to disappoint the full meeting which had for some time been waiting for him, he went forth almost at the end of the fifth hour (11:00 AM); and when a note revealing the plot was handed him by someone on the way, he put it with others which he held in his left hand, intending to read them presently. Then, after several victims had been slain, and he could not get favorable omens, he entered the House in defiance of portents, laughing at Spurinna and calling him a false prophet, because the Ides of March were come without bringing him harm; though Spurinna replied that they had of a truth come, but they had not gone. As he took his seat, the conspirators gathered about him as if to pay their respects, and straightway Tillius Cimber, who had assumed the lead, came nearer as though to ask something; and when Caesar with a gesture put him off to another time, Cimber caught his toga by both shoulders; then as Caesar cried, ‘Why, this is violence!’ one of the Cascas stabbed him from one side just below the throat. Caesar caught Casca’s arm and ran it through with his stylus, but as he tried to leap to his feet, he was stopped by another wound.

When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered. And in this wise he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, ‘You too, my child?’

When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered. And in this wise he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, ‘You too, my child?’

All the conspirators made off, and he lay there lifeless for some time, and finally three common slaves put him on a litter and carried him home, with one arm hanging down. And of so many wounds none turned out to be mortal, in the opinion of the physician Antistius, except the second one in the breast. The conspirators had intended after slaying him to drag his body to the Tiber, confiscate his property, and revoke his decrees; but they forebore through fear of Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) the consul, and Lepidus, the master of horse.”—Article by Sandra Sweeny Silver