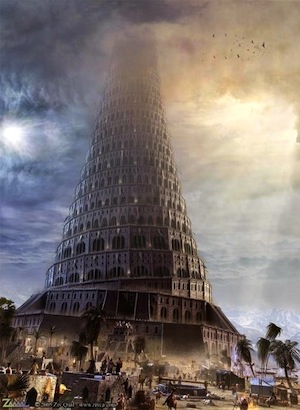

Early post-flood civilization began in Iraq in the fertile crescent of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. The Tower of Babel where the languages were confused (we get our word “babble” from that incident) was in Iraq. (Genesis 11:1-9)

Abraham, the father of the Jews and Arabs came from Ur in Iraq. (Genesis 11:3-32) Abraham picked a bride from Iraq for his son Isaac. (Genesis 24:3-10) Jacob, Isaac’s son, spent c. 20 years in Iraq. (Genesis 27:42-45; 31:38) The Babylonian Empire in Iraq attacked the Jews and Jerusalem fell to them in c. 588 BC. Significant numbers of the Jews were taken to Babylon in Iraq where they remained in captivity for 70 years. These were the days of the prophet Daniel (c. 770-750 BC) of the Lion’s Den fame who died a captive but respected wise man in Iraq.

Jonah, writing c. 785-750 BC, was the prophet who did not want to tell Nineveh in Iraq to repent and was swallowed by a giant fish. On Nabi hill of Yunus in Iraq near Mosul a shrine dedicated to Jonah, believed to contain his tomb, was a site of pilgrimage for both Muslims and Christians. People from all over the world came to see this ancient shrine. On July 14, 2014, ISIS destroyed the tomb because they thought it was idolatrous.

The events in the book of Esther take place in Iraq. (c. 460 BC) The Biblical prophet Nahum prophesied against Iraq. (Nahum 1:1-14) The New Testament contains prophecies against a figurative Babylon in Iraq in the End Times. (Revelation 17-18) The Old Testament is mainly about the Jews, but second to Israel, Iraq is the most mentioned nation in the Old Testament. Doubting Thomas and other early disciples brought Christianity to Iraq in the 1st century AD. The northern parts of Iraq became the center of the Eastern Rite of Christianity and Christian literature from the 1st century until the Middle Ages.

The looting of the Baghdad Museum on April 10 – 12 of 2003 was not only a looting of Iraq’s heritage and world heritage, but of the heritage of the Jews and the Christians, also. In 2015 the Iraq Museum in Baghdad re-opened 12 years after the looting. Most of the lost artifacts have been found or returned, but there are still a significant amount that have been lost or have found their way into the thriving, illegal market for stolen artifacts. Below is a fascinating 48 minute video about stolen Roman treasure.—Sandra Sweeny Silver

The article below, “The Looting Of The Baghdad Museum On April 2003” by Robert M. Poole, was published in Smithsonian Magazine, February 2003

No one was prepared for the pillaging of Baghdad’s Iraq Museum in April 2003, but a fast-thinking Marine officer Col. Matthew Bogdanos, improvised an investigation—and helped recover thousands of stolen antiquities. The thieves took or destroyed 15,000 archeological treasures from thousands of years ago and when they looted the National Library in Baghdad the same month, they destroyed and burned one million books and ancient documents including ancient copies of the Koran.

Looting has been a part of war at least since 333 B.C., when Alexander the Great strolled into the tent of King Darius III, helped himself to the vanquished Persian’s best tapestries and commandeered the royal bathtub for a soothing victory soak. In the years since, victors have taken the spoils, and in their wake, ordinary citizens and opportunistic thieves have grabbed anything of value in that confused pause between war and peace.

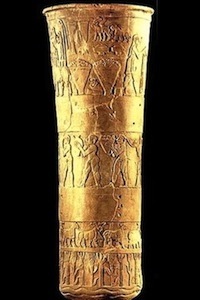

All the looting at Baghdad’s Iraq Museum had taken place by the time U.S. troops—engaged in toppling Saddam Hussein—arrived to protect it on April 16, 2003. Between April 8, when the museum was vacated, and April 12, when the first of the staff returned, clubs in hand, thieves had plundered 15,000 items, many of them choice antiquities: ritual vessels, heads from sculptures, amulets, Assyrian ivories and more than 5,000 cylinder seals.

The looting proved less extensive than the early reports of 170,000 stolen artifacts, but the losses were nonetheless staggering. “Every single item that was lost is a great loss for humanity,” says Donny George Youkhanna, the former director general of Iraqi museums, now a visiting professor at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. “It is the only museum in the world where you can trace the earliest development of human culture—technology, agriculture, art, language and writing—in just one place.”

Before the war, leading archaeologists had warned that the museum was vulnerable, but neither Iraqi officials nor invading troops were prepared for such aggressive plunder. There was nothing like the World War II-era Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives task force poised to secure, track down and recover Iraq’s venerable treasures. But there was the ‘Pit Bull,’ also known as Marine Col. Matthew Bogdanos, a reservist, classics scholar and amateur boxer, who had earned his civilian nickname as a homicide prosecutor in New York City.

“I felt exactly the way the rest of the world did—outraged—when I heard of the looting in Baghdad,” says Bogdanos, who was leading a counterterrorist unit in southern Iraq when he learned of the pillaging. He quickly got permission from the U.S. Central Command to form an ad hoc “Monuments” team, composed of 14 members with investigative experience. Bogdanos and his team dashed north to Baghdad, arriving April 20. They established security at the museum complex and, huddling with museum authorities, began an inventory of missing treasures. They dispatched descriptions to border guards, customs agents, international police agencies and archaeologists around the world. They put out the word that no one returning stolen items would be prosecuted. “If you bring something back to the museum,” Bogdanos was fond of saying, “the only question you will be asked is whether you would like a cup of tea.”

Over the next few weeks, stolen goods began to trickle back, including a 6000 B.C. pot wrapped in a 21st-century garbage bag and the Sacred Vase of Warka (c. 3200 B.C.), in the trunk of a car. Objects were unearthed from backyards, fished out of a cesspool, recovered in pre-dawn raids. Some simply reappeared on museum shelves.

Other treasures were seized from international antiquities markets in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and New York. A scholar returning from the war zone was collared at John F. Kennedy International Airport and convicted of smuggling three 4,000-year-old cylinder seals from the museum’s collection.

“Mothers turned in items stolen by their sons,” says Bogdanos. “Sons turned in items stolen by their friends. Employees turned in items stolen by their bosses.”

“Mothers turned in items stolen by their sons,” says Bogdanos. “Sons turned in items stolen by their friends. Employees turned in items stolen by their bosses.”

And as the investigation unfolded, it developed that hundreds of the most valuable items missing from the museum—including a cache of gold jewelry from Nimrud—had not been stolen at all but stashed, since the Gulf War of 1990-91, for safekeeping in Iraq’s Central Bank.

George (Donny George Youkhanna) estimates that about half of the 15,000 looted treasures have either been returned or secured in other countries until they can be safely repatriated. Still missing are thousands of cylinder seals, a famous eighth-century B.C. gold-and- ivory plaque known as The Lioness Attacking a Nubian and choice pieces of statuary from the ancient city of Hatra. An optimist with an archaeologist’s long view of history, George believes that in the fullness of time, all of the antiquities will be returned. Meanwhile, many of Iraq’s 12,500 archaeological sites continue to be vulnerable to looting, and the Iraq Museum remains closed, its treasures bricked up within interior storage rooms. “The museum must be the last place to be opened after everything else is completely secured in the country,” says George.

After two tours in Iraq and service in the Horn of Africa and at the Pentagon, Bogdanos returned home to New York City in 2005, in time for the publication of his book, Thieves of Baghdad.

After two tours in Iraq and service in the Horn of Africa and at the Pentagon, Bogdanos returned home to New York City in 2005, in time for the publication of his book, Thieves of Baghdad.  (All royalties are being donated to the Iraq Museum.) He continues to investigate the Iraqi thefts as chief of a newly created antiquities task force in the New York County district attorney’s office. “Until every last piece stolen from the Iraqi Museum has been recovered and returned to the Iraqi people,” he says, “I will continue to be haunted by what is still missing,” says Bogdanos.—End of Smithsonian Magazine article. CLICK HERE to order Thieves of Baghdad.

(All royalties are being donated to the Iraq Museum.) He continues to investigate the Iraqi thefts as chief of a newly created antiquities task force in the New York County district attorney’s office. “Until every last piece stolen from the Iraqi Museum has been recovered and returned to the Iraqi people,” he says, “I will continue to be haunted by what is still missing,” says Bogdanos.—End of Smithsonian Magazine article. CLICK HERE to order Thieves of Baghdad.

The Baghdad Museum officially reopened in February 2015. At the same time in February 2015, ISIS was destroying with sledgehammers and drills artifacts in the Museum in Mosul. This one minute ISIS video captures that incident.