The most amazing spectacles of them all in the Colosseum were the naumachia, mock sea battles. These were reenactments on water of historical naval battles with condemned criminals as sailors. The first naumachia was given by Julius Caesar in 46 BC to celebrate his victories in Egypt. Caesar created a basin near the Tiber River on the Campus Martius and flooded it. Sixteen life-size ships manned by 4,000 rowers and 2,000 slaves reenacted a battle between the Egyptians and the Tyrians. It was a fight to the death for men and rowers. Caesar had a special coin minted portraying this first-of-a-kind spectacle.

Emperor Augustus, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, celebrated the inauguration of a temple to Mars, the god of war, in 2 BC with the second naumachia. He describes it in his The Deeds 23:

“I gave the people a naval battle in the place across the Tiber where the grove of the Caesars is now, with the ground excavated in length 1,800’, in width 1,200’, in which 30 beaked ships, biremes and triremes, but many smaller, fought among themselves. In the ships about 3,000 men fought in addition to the rowers.”

In that small pretend ocean, the pretend sailors with real weapons were packed in like sardines. They reenacted the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) in which a powerful Persian army attacked a weak Greek contingent off the island of Salamis. The Greeks won. In this sham naval battle, the criminals were dressed like Persians and Greeks.

It boggles the mind to imagine the sophisticated engineering and the minute preparations for this and other naumachia: the construction and filling of the basin by a specially built aqueduct (remains of which are still visible in Rome below the monastery of St. Cosimato), the making and fitting of the costumes, the brief education the combatants had to receive in order to know what they were doing, the building of the bleachers for the spectators, the advertising for the event, secure transportation of the criminals to the scene and getting them on the boats and deciding when the battle would begin, and…. Think of how many thousands of men/slaves, many of them Christians, had to work thousands of hours for an afternoon of entertainment for the masses. And the bloody cleanup.

Of course, for Augustus’ naumachia he had his eye on Julius’ naumachia forty-four years earlier and wanted to make sure his spectacle exceeded that of his adoptive father. The cost? Who knows? The criminal actors were free. Many Christians were slaves in Rome in  the mid-1st century and some of their free slave labor dug the basin, built the aqueduct, built the ships, made the costumes. And there had to have been highly educated Romans who engineered and profited from this whole extravaganza. In this mock battle, if you multiply the number of fighting men (3,000) by two, there were 6,000 rowers. A total of 9,000 men, more than a standard Roman fleet, fought. It is unlikely that many of them survived the battle. Again, that was the point.

the mid-1st century and some of their free slave labor dug the basin, built the aqueduct, built the ships, made the costumes. And there had to have been highly educated Romans who engineered and profited from this whole extravaganza. In this mock battle, if you multiply the number of fighting men (3,000) by two, there were 6,000 rowers. A total of 9,000 men, more than a standard Roman fleet, fought. It is unlikely that many of them survived the battle. Again, that was the point.

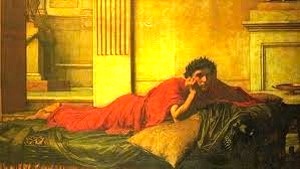

Nero in 57 was the first to give a naumachia in an amphitheater. The amphitheater was a wooden one on the Campus Martius. We do not know much about this building, but Suetonius in Lives Of The Caesars relates an interesting incident that occurred one day at that amphitheater. It was during one of the reenactments of the popular Icarus’ and Daedalus’ “attempt at flying” story:

“Icarus (played by a condemned criminal) at his very first attempt (at flight from the top of the building) fell close by (Nero’s) couch and bespattered the emperor with his blood, for Nero very seldom presided at the games, but used to view them while reclining on a couch.”

Suetonius’ whole point in telling this bloody story was not to call attention to doomed Icarus but to emphasize the fact that Nero rarely presided at the games. He “peeked” at them from an opening in the curtain and was besmirched.

When the travertine and cement Colosseum was opened and officially inaugurated in 80 AD, Emperor Titus declared one hundred days of celebration. On the first day of the celebration, Titus treated the people to a twenty-four hour extravaganza. Everything he had organized was like the finale of a fire-works display:

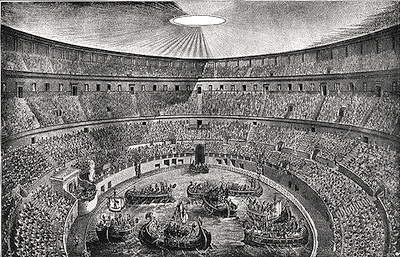

“…remarkable spectacles….a battle between cranes and also between four elephants; animals both tame and wild were slain to the number of 9,000….women, but not those of any prominence, took part in dispatching them….and naval battles. For Titus suddenly filled this same theater (Colosseum) with water and brought in horses and bulls and some other domesticated animals that had been taught to behave in the liquid element just as on land. He also brought in people on ships who engaged in a sea fight there, impersonating the Corcyreans (from Corfu) and the Corinthians….There, too, on this first day there was a gladiatorial exhibition and wild beast hunt.” Cassius Dio, Roman History 66.25.1-5

Scholars have speculated for centuries on how the Colosseum was filled with water sufficient for a mock battle to take place. Martial who was at the Colosseum that day in 81 says:

“There was land until a moment ago. Can you doubt it? Wait until the water, draining away puts an end to the combats. It will happen right away and you will say: the sea was there a moment ago.” On The Spectacles 24

The arena was obviously flooded and drained seamlessly. After the opening animal hunt was dismantled, landscaping carted away, dead animals dragged out and the area cleaned up, the people talked, laughed and waited for the next show. What’s that? Water! Gushing and rushing in. Some in the audience start the rumor that a naumachia will take place. The last spectacle like that was twenty-five years ago. Some in the crowd were too young to have seen one. The water continues to fill up the arena until it is of sufficient depth. Then what? Do they bring in the big, life-size triremes and all the thousands of combatants dressed like Corcyreans and Corinthians?

How did they get those standard-sized ships with all the combatants aboard into the flooded arena without letting out the water? Maybe they first placed the ships and men into the arena and then turned the floodgates loose? We know there were pipes for carrying the water into the arena, but exactly how did they get the water for the naumachia into and then out of the arena in such a short time? Was the arena watertight? It had to have been. Many, many questions over the last 2,000 years. The fact remains: we do not know exactly how the Romans placed all the “soldiers” and paraphernalia into the arena and then flooded and drained the Colosseum just as we do not know how the Egyptians built the Pyramid of Cheops. We do know that on that first day of celebration, the animal hunt was first, the naval battle was second and then the amphitheater was drained and dry (not muddy) because next “there was a gladiatorial exhibition and (another) wild-beast hunt.” The second day there was a chariot race. The third day there was another flooding of the Colosseum with “a naval battle between 3,000 men….The Athenians conquered the Syracusans…(who) made a landing on the islet (that had been created in the middle of the Colosseum) and assaulted and captured a wall that had been constructed around the monument. These were the spectacles.”—Sandra Sweeny Silver

CLICK HERE to see a full article on the Colosseum.